State-led Rural Transformation: The Case of Yukarıköy

Master of Architecture Thesis | Middle East Technical University | 2022

Overview

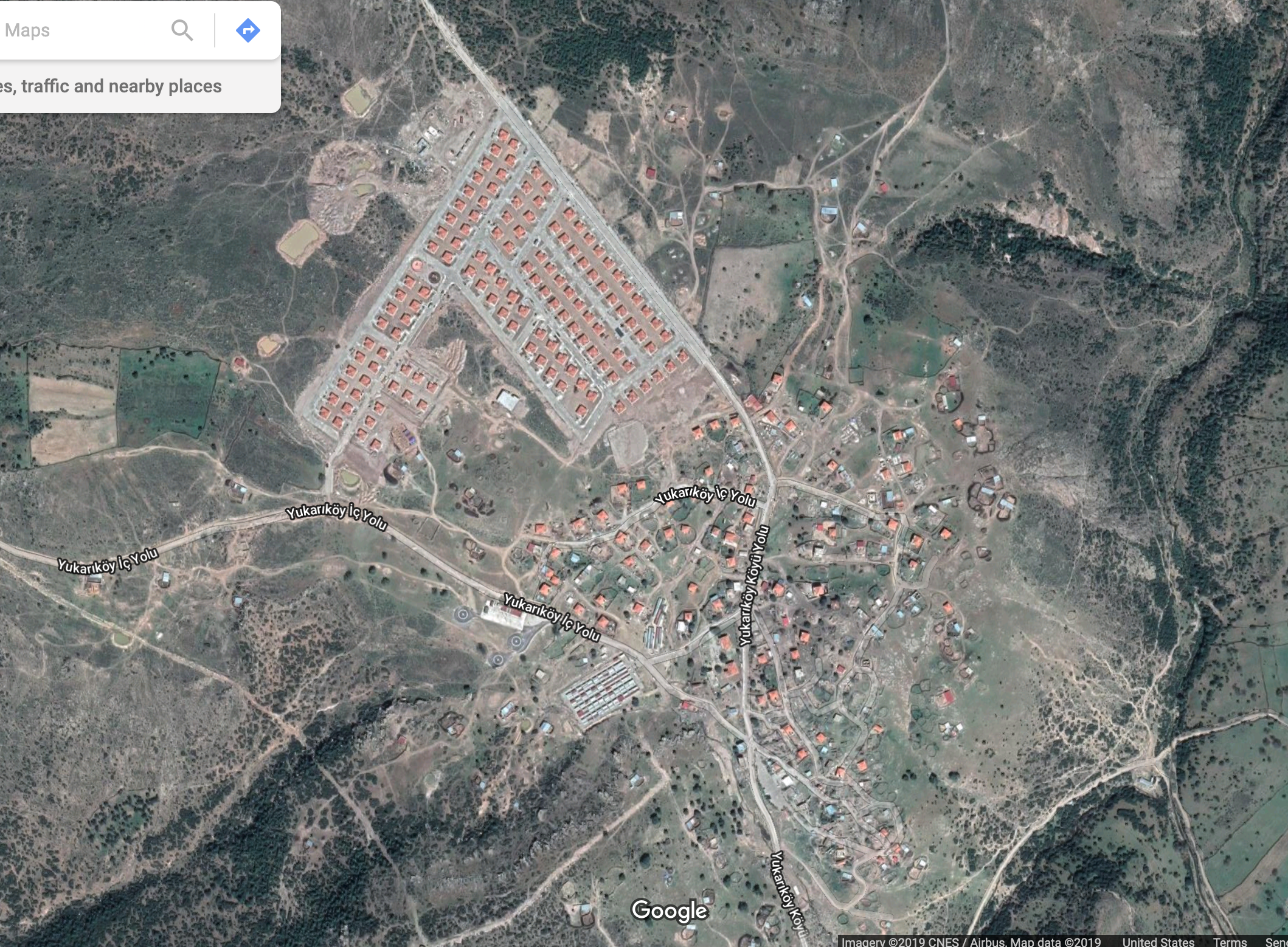

How do people inhabit spaces designed for them by governing institutions? My thesis explored this question through ethnographic research in Yukarıköy, a Yörük village in Çanakkale, Turkey, where 166 houses were rebuilt by the state's Housing Development Administration (TOKİ) following destructive earthquakes in 2017. While TOKİ's urban transformation projects are widely documented, their rural interventions remain underexplored. Through fieldwork spanning multiple visits between 2020-2022, I examined how the state's vision of "modernizing" rural life intersected with villagers' actual practices—revealing how inhabitants both adapt to and reshape strategically planned environments through everyday tactics.

Research Questions

• How is space in rural Turkey produced through the interplay of state strategies and inhabitants' everyday practices?

• In what ways do villagers appropriate TOKİ-designed houses according to their own needs while navigating state expectations?

• What happens when neoliberal housing policy—designed to create "customer-citizens"—meets the lived realities of rural communities?

Methodology

This research employed qualitative ethnographic methods, combining:

• Historical analysis of state rural interventions from the Ottoman Empire through TOKİ (1850-present)

• Spatial analysis using Lefebvre's spatial triad (perceived, conceived, and lived space)

• Field observation across multiple visits (2020-2022) documenting how villagers modified and inhabited the new houses

• Informal interviews with residents about their experiences, challenges, and adaptations

The theoretical framework drew from Judith Butler's work on performativity, Michel de Certeau's concepts of strategies and tactics, and Michel Foucault's analysis of power relations—providing tools to understand how space both shapes and is shaped by everyday practices.

Key Findings

The Production of "Customer-Citizens": Unlike TOKİ's profit-driven urban projects that displace residents, Yukarıköy's earthquake houses weren't built for financial gain. However, the neoliberal logic remained: villagers became long-term debtors paying installments to the state over 20 years, transforming inhabitants into customer-citizens even without displacement.

Spatial Tactics Within Strategic Design: Residents immediately began adapting their new homes—building stone ovens for traditional bread-making, constructing outdoor toilets despite two indoor bathrooms, adding one-room houses for elderly parents, and converting porches into carpet-weaving workshops. These weren't acts of resistance but inventive tactics for continuing valued practices within new spatial constraints.

Historical Continuity: Comparing Yukarıköy to projects from Sample Villages (1920s-30s) through Village Institutes (1940s) revealed consistent patterns: the state repeatedly attempts to "modernize" rural citizens through architectural intervention, while inhabitants consistently find ways to make spaces work for them rather than adapting entirely to prescribed uses.

Connecting This Research to My Design Practice

Users as Active Producers: Yukarıköy demonstrates that people don't simply accept designed systems—they adapt, modify, and work around them. Digital designers face similar realities: users develop workarounds, repurpose features, and create use cases designers never imagined.

Power and Equity in Design: Who decides how systems should work? My research examined how institutional power shapes environments, but also how inhabitants push back. Understanding these dynamics is essential for creating more equitable digital systems.

Context Over Standardization: TOKİ applied standardized approaches used since Ottoman-era village projects, ignoring local practices. The result required costly adaptation by both state and citizens. In UX, understanding specific contexts and community needs must drive design decisions rather than one-size-fits-all solutions.

Ethnography as Design Tool: Observing how villagers transformed their spaces revealed needs that surveys would miss. Ethnographic methods—watching behavior in context, understanding workarounds, documenting adaptations—uncover actual user needs rather than assumed ones.

👋🏻 Personal Notes

This research was deeply personal—Yukarıköy is close to where I'm from in Çanakkale. The saying "write what you know" took on new meaning as I studied a place I thought I understood but came to know in entirely new depth through this work.

Being from the region mattered. The villagers already knew me or my family, which transformed what could have been formal interviews into shared meals, tea, and genuine conversations. I even attended a wedding there. This insider perspective was crucial—when academics discuss Yörük villages, there's often an undertone of pity or romanticization, assumptions about rural poverty. But I knew these villagers aren't poor. They do agriculture, animal husbandry, run carpet-weaving businesses. They have resources and agency. My research approach refused both pity and romanticization, instead focusing on how people with clear intentions and capabilities navigate state-imposed systems.

Yukarıköy taught me that good design isn't about controlling use—it's understanding the relationship between what's provided and what's practiced, between strategic design and tactical adaptation.